Imagine Zora Neal Hurston as a Cieba tree

or Miles Davis as a stone by the mouth of the Nile

Perhaps Shaka Zulu a cavern beneath the nations soil.

or Essex Hemphill a open field of lavender

Spirit of Place

Spirit of place (or soul) refers to the unique, distinctive and cherished aspects of a place; often those celebrated by artists and writers, but also those cherished in folk tales, festivals and celebrations. It is thus as much in the invisible weave of culture (stories, art, memories, beliefs, histories, etc.) as it is the tangible physical aspects of a place (monuments, boundaries, rivers, woods, architectural style, rural crafts styles, pathways, views, and so on) or its interpersonal aspects (the presence of relatives, friends and kindred spirits, and the like).[citation needed]

Often the term is applied to a rural or a relatively unspoiled or regenerated place — whereas the very similar term sense of place would tend to be more domestic, urban, or suburban in tone. For instance, one could logically apply 'sense of place' to an urban high street; noting the architecture, the width of the roads and pavements, the plantings, the style of the shop-fronts, the street furniture, and so on, but one could not really talk about the 'spirit of place' of such an essentially urban and commercial environment. However, an urban area that looks faceless or neglected to an adult may have deep meaning in children's street culture.[original research?]

The Roman term for spirit of place was Genius loci, by which it is sometimes still referred. This has often been historically envisaged as a guardian animal or a small supernatural being (puck, fairy, elf, and the like) or a ghost. In the developed world these beliefs have been, for the most part, discarded. A new layer of less-embodied superstition on the subject, however, has arisen around ley lines, feng shui and similar concepts, on the one hand, and urban leftover spaces, such as back alleys or gaps between buildings in some North-American downtown areas, on the other hand.[1]

The western cultural movements of Romanticism and Neo-romanticism are often deeply concerned with creating cultural forms that 're-enchant the land', in order to establish or re-establish a spirit of place.[2]

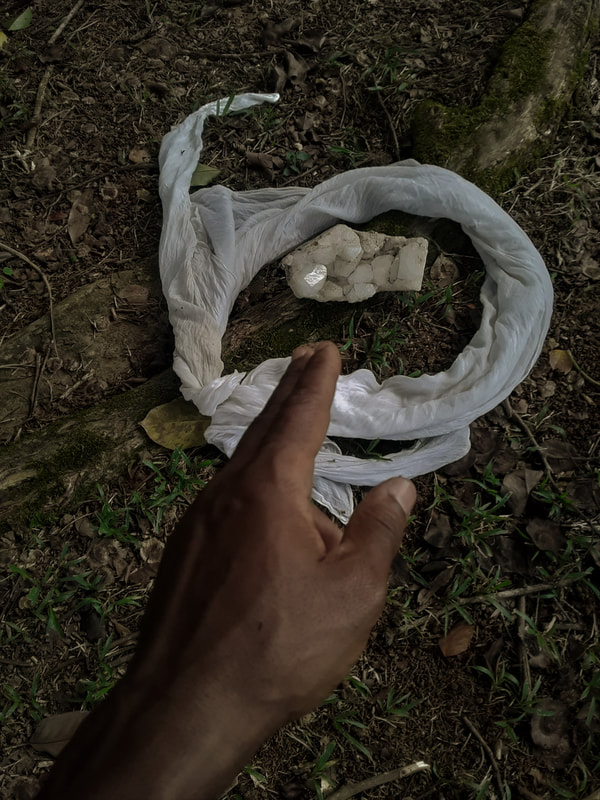

Modern earth art (sometimes called environment art) artists such as Andy Goldsworthy have explored the contribution of natural/ephemeral sculpture to spirit of place.[3][4]

Many indigenous and tribal cultures around the world are deeply concerned with spirits of place in their landscape.[5] Spirits of place are explicitly recognized by some of the world's main religions: Shinto has its Kami which may incorporate spirits of place; and the Dvarapalas and Lokapalas in Hinduism, Vajrayana and Bonpo traditions.

Ecology and the ancestors

Over the course of my dealings with memorials, historic sites and cultural remains I have come to realize its all a matter of energy. be it a A grove where mourning rituals occurred in times past or the foot print of a once bustling market square, indigenous ceremonial ground

Nature spirit is really an umbrella term, a bit like saying animal or plant. It simply denotes a being that works with the spiritual and energetic side of nature. However, just as there are billions of different species of plants and animals on earth, so there are at least as many different kinds of “nature spirits.” In some ways, it’s a meaningless phrase because it’s so broad and all-encompassing. A nature spirit is usually a being that is defined by a particular relationship with some specific form or function within the natural environment of the earth. By necessity, such beings, while their origin and fuller natures may be in the higher-order worlds, take form and work within the transitional realms and the subtle energy fields of the physical worlds. They tie themselves to specific landscapes and to geographical features such as rivers, and to species of plants and animals, and even to the individual plants themselves.

Through site specific ritual arts we are able to explore these and similar energetic phenomena harness disperse and collaborate with these nature spirits and expand various areas of our consciousness.

how sites of memorial and commemoration can serve as energetic portals for spiritual transformation.

Deep Map Making explorations

A deep map is a map with greater information than a two-dimensional image of places, names, and topography.

One such kind of intensive exploration of place was popularised by author William Least Heat-Moon with his book PrairyErth: A Deep Map. A deep map work can take the form of engaged documentary writing of literary quality. It may be performed in long-form on radio. It does not preclude the combination of writing with photography and illustration. Its subject is a particular place, usually quite small and limited, and usually rural.

Some[who?] call the approach "vertical travel writing", while archeologist Michael Shanks compares it to the eclectic approaches of 18th- and early-19th-century antiquarian topographers or to the psychogeographic excursions of the early Situationist International.[1][2]

Such a deep map goes beyond simple landscape/history-based topographical writing to include and interweave autobiography, archeology, stories, memories, folklore, traces, reportage, weather, interviews, natural history, science, and intuition. In its best form, the resulting work arrives at a subtle, multi-layered and "deep" map of a small area of the earth.

US scholars and writers of bioregionalism have promoted the concept of deep maps. The best known US examples are Wallace Stegner's Wolf Willow (1962) and Heat-Moon's PrairyErth (1991).

In Great Britain, the method is used by those who use the terms spirit of place and local distinctiveness. BBC Radio 4 has recently undertaken several series of radio documentaries that are deep maps. These are inspired by the "sense of place" work of the Common Ground organisation.

As used in the field of geographical information systems, deep maps have more kinds of information than 2D images with labels. They may have 3D information, census information, health or immigrant or education information; information on particular buildings, museum artifacts and where they are from, and the overall demographics of cities. They can link places to documents about their history. They can help support subjective descriptions, and narratives.

or Miles Davis as a stone by the mouth of the Nile

Perhaps Shaka Zulu a cavern beneath the nations soil.

or Essex Hemphill a open field of lavender

Spirit of Place

Spirit of place (or soul) refers to the unique, distinctive and cherished aspects of a place; often those celebrated by artists and writers, but also those cherished in folk tales, festivals and celebrations. It is thus as much in the invisible weave of culture (stories, art, memories, beliefs, histories, etc.) as it is the tangible physical aspects of a place (monuments, boundaries, rivers, woods, architectural style, rural crafts styles, pathways, views, and so on) or its interpersonal aspects (the presence of relatives, friends and kindred spirits, and the like).[citation needed]

Often the term is applied to a rural or a relatively unspoiled or regenerated place — whereas the very similar term sense of place would tend to be more domestic, urban, or suburban in tone. For instance, one could logically apply 'sense of place' to an urban high street; noting the architecture, the width of the roads and pavements, the plantings, the style of the shop-fronts, the street furniture, and so on, but one could not really talk about the 'spirit of place' of such an essentially urban and commercial environment. However, an urban area that looks faceless or neglected to an adult may have deep meaning in children's street culture.[original research?]

The Roman term for spirit of place was Genius loci, by which it is sometimes still referred. This has often been historically envisaged as a guardian animal or a small supernatural being (puck, fairy, elf, and the like) or a ghost. In the developed world these beliefs have been, for the most part, discarded. A new layer of less-embodied superstition on the subject, however, has arisen around ley lines, feng shui and similar concepts, on the one hand, and urban leftover spaces, such as back alleys or gaps between buildings in some North-American downtown areas, on the other hand.[1]

The western cultural movements of Romanticism and Neo-romanticism are often deeply concerned with creating cultural forms that 're-enchant the land', in order to establish or re-establish a spirit of place.[2]

Modern earth art (sometimes called environment art) artists such as Andy Goldsworthy have explored the contribution of natural/ephemeral sculpture to spirit of place.[3][4]

Many indigenous and tribal cultures around the world are deeply concerned with spirits of place in their landscape.[5] Spirits of place are explicitly recognized by some of the world's main religions: Shinto has its Kami which may incorporate spirits of place; and the Dvarapalas and Lokapalas in Hinduism, Vajrayana and Bonpo traditions.

Ecology and the ancestors

Over the course of my dealings with memorials, historic sites and cultural remains I have come to realize its all a matter of energy. be it a A grove where mourning rituals occurred in times past or the foot print of a once bustling market square, indigenous ceremonial ground

Nature spirit is really an umbrella term, a bit like saying animal or plant. It simply denotes a being that works with the spiritual and energetic side of nature. However, just as there are billions of different species of plants and animals on earth, so there are at least as many different kinds of “nature spirits.” In some ways, it’s a meaningless phrase because it’s so broad and all-encompassing. A nature spirit is usually a being that is defined by a particular relationship with some specific form or function within the natural environment of the earth. By necessity, such beings, while their origin and fuller natures may be in the higher-order worlds, take form and work within the transitional realms and the subtle energy fields of the physical worlds. They tie themselves to specific landscapes and to geographical features such as rivers, and to species of plants and animals, and even to the individual plants themselves.

Through site specific ritual arts we are able to explore these and similar energetic phenomena harness disperse and collaborate with these nature spirits and expand various areas of our consciousness.

how sites of memorial and commemoration can serve as energetic portals for spiritual transformation.

Deep Map Making explorations

A deep map is a map with greater information than a two-dimensional image of places, names, and topography.

One such kind of intensive exploration of place was popularised by author William Least Heat-Moon with his book PrairyErth: A Deep Map. A deep map work can take the form of engaged documentary writing of literary quality. It may be performed in long-form on radio. It does not preclude the combination of writing with photography and illustration. Its subject is a particular place, usually quite small and limited, and usually rural.

Some[who?] call the approach "vertical travel writing", while archeologist Michael Shanks compares it to the eclectic approaches of 18th- and early-19th-century antiquarian topographers or to the psychogeographic excursions of the early Situationist International.[1][2]

Such a deep map goes beyond simple landscape/history-based topographical writing to include and interweave autobiography, archeology, stories, memories, folklore, traces, reportage, weather, interviews, natural history, science, and intuition. In its best form, the resulting work arrives at a subtle, multi-layered and "deep" map of a small area of the earth.

US scholars and writers of bioregionalism have promoted the concept of deep maps. The best known US examples are Wallace Stegner's Wolf Willow (1962) and Heat-Moon's PrairyErth (1991).

In Great Britain, the method is used by those who use the terms spirit of place and local distinctiveness. BBC Radio 4 has recently undertaken several series of radio documentaries that are deep maps. These are inspired by the "sense of place" work of the Common Ground organisation.

As used in the field of geographical information systems, deep maps have more kinds of information than 2D images with labels. They may have 3D information, census information, health or immigrant or education information; information on particular buildings, museum artifacts and where they are from, and the overall demographics of cities. They can link places to documents about their history. They can help support subjective descriptions, and narratives.

| ecological_implications_of_wata_spirits.pdf | |

| File Size: | 53 kb |

| File Type: | |